Kimwolf Exposed: The Massive Android Botnet with 1.8 Million Infected Devices

Background

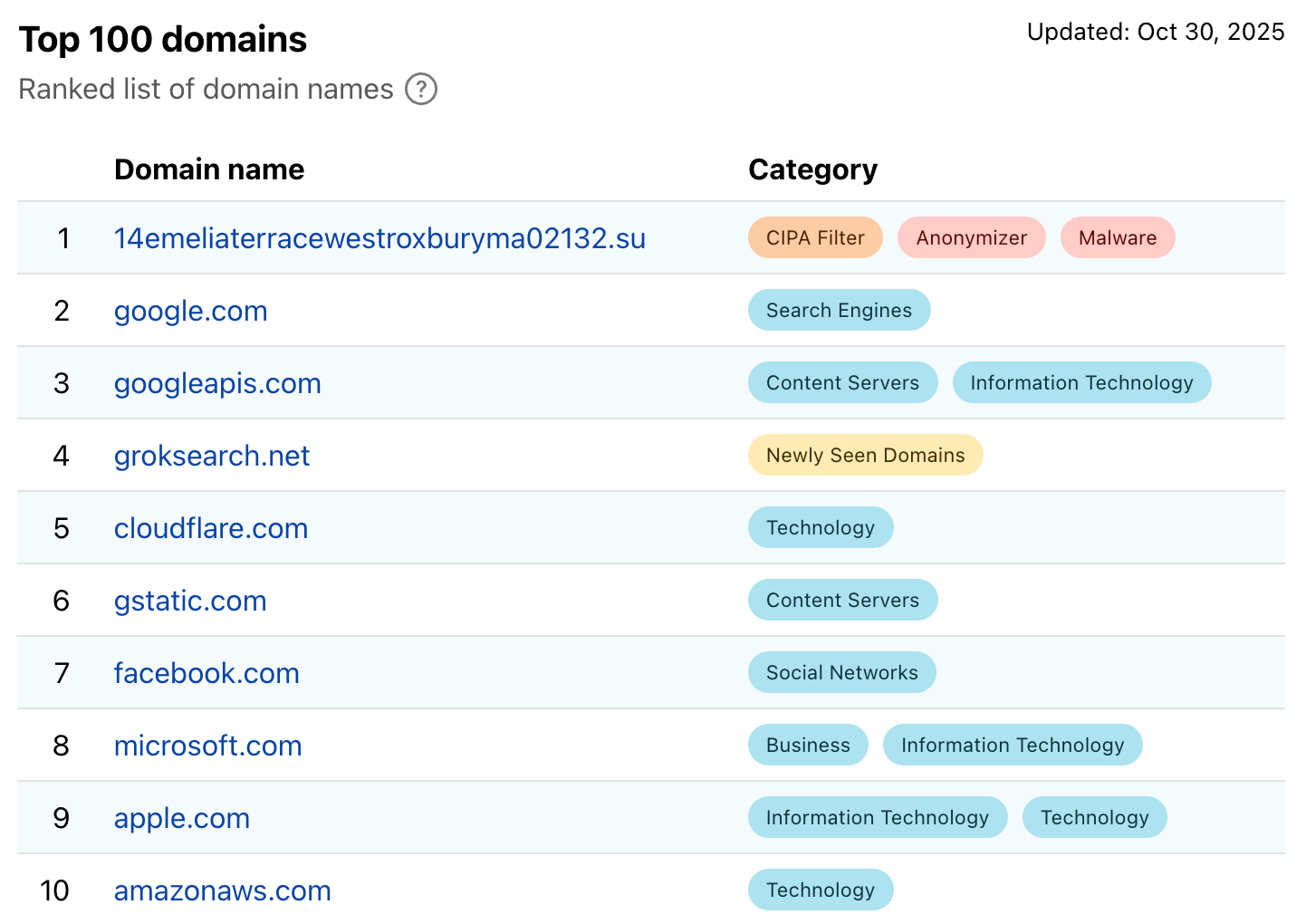

On October 24, 2025, a trusted partner in the security community provided us with a brand-new botnet sample. The most distinctive feature of this sample was its C2 domain, 14emeliaterracewestroxburyma02132[.]su, which at the time ranked 2nd in the Cloudflare Domain Rankings. A week later, it even surpassed Google to claim the number one spot in Cloudflare's global domain popularity rankings. There is no doubt that this is a hyper-scale botnet. Based on the information output during runtime and its use of the wolfSSL library, we have named it Kimwolf.

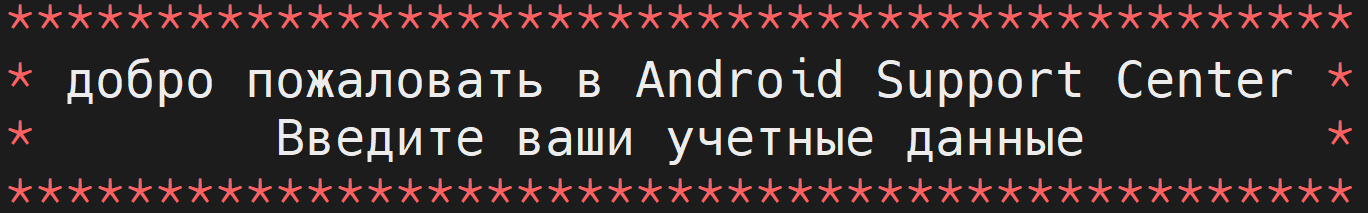

Kimwolf is a botnet compiled using the NDK. In addition to typical DDoS attack capabilities, it integrates proxy forwarding, reverse shell, and file management functions. From an overall architectural perspective, its functional design is not complex, but there are some highlights worth noting: for example, the sample uses a simple yet effective Stack XOR operation to encrypt sensitive data; meanwhile, it utilizes the DNS over TLS (DoT) protocol to encapsulate DNS requests to evade traditional security detection. Furthermore, its C2 identity authentication employs a digital signature protection mechanism based on elliptic curves, where the Bot side will only accept communication instructions after the signature verification passes. Recently, it has even introduced EtherHiding technology to counter takedowns using blockchain domains. These features are relatively rare in similar malware. Based on our analysis results, it primarily targets Android platform TV boxes. The "Welcome to Android Support Center" message displayed on the C2 backend also corroborates this.

The Kimwolf samples use a naming rule of "niggabox + v[number]" to identify version numbers. The sample previously provided by our community partner was version v4. After completing the reverse engineering analysis, we imported the sample's intelligence into the XLab's Cyber Threat Insight and Analysis System, successively capturing multiple related samples including v4 and v5, achieving automated continuous tracking of this family.

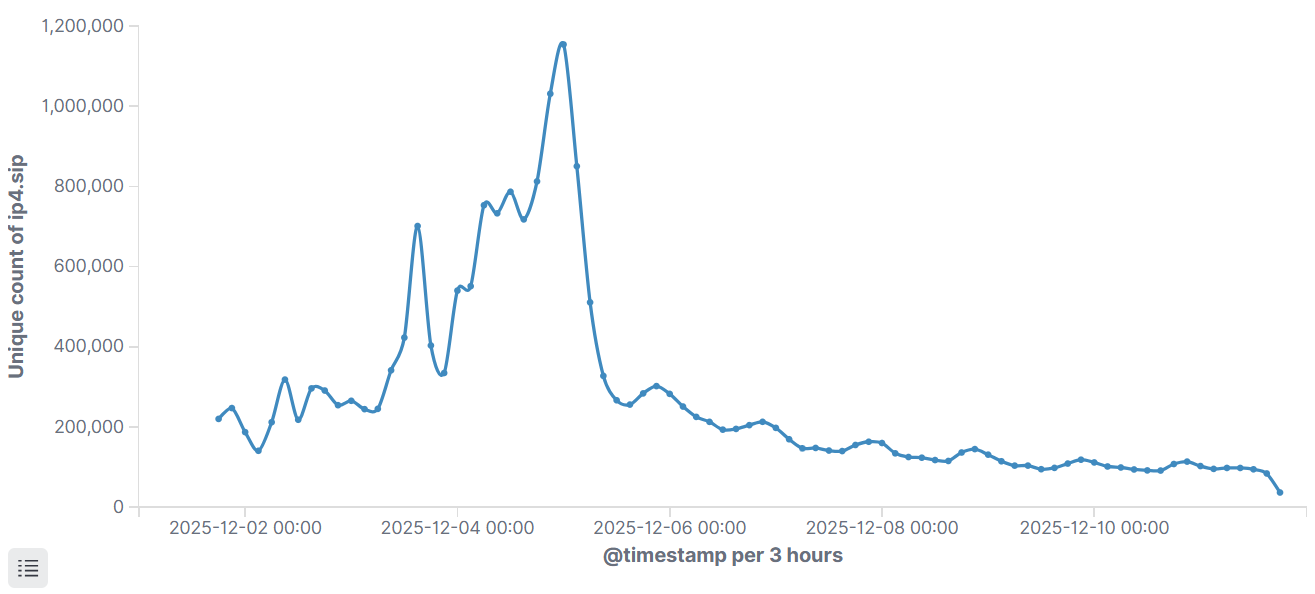

On November 30, we captured another new sample of this botnet family and successfully took over one of the C2 domains, thereby obtaining the opportunity to directly observe the true operating scale of this botnet for the first time. Based on statistics from source IP data that established connections with our registered C2 address and whose communication behavior matched Kimwolf C2 protocol characteristics, we observed a cumulative total of approximately 2.7 million distinct source IP addresses over the three days from December 3 to December 5. Among them, we observed approximately 1.36 million active IPs on December 3, about 1.83 million on December 4, and about 1.5 million on December 5 (there is IP overlap between different dates). Analysis indicates that Kimwolf's primary infection targets are TV boxes deployed in residential network environments. Since residential networks usually adopt dynamic IP allocation mechanisms, the public IPs of devices change over time, so the true scale of infected devices cannot be accurately measured solely by the quantity of IPs. In other words, the cumulative observation of 2.7 million IP addresses does not equate to 2.7 million infected devices.

Despite this, we still have sufficient reason to believe that the actual number of devices infected by Kimwolf exceeds 1.8 million. This judgment is based on observations in the following areas:

- Kimwolf uses multiple C2 infrastructures. We took over only a portion of the C2s, so we could only observe the activity of some Bots, unable to cover the full picture of the botnet.

- On December 4, the number of Bot IPs we observed reached approximately 1.83 million, a historical peak. On that day, parts of the C2s normally used by Kimwolf were taken down by relevant organizations, causing a large number of Bots to fail to connect to the original C2s and turn to try connecting to the C2 we preemptively registered. This anomalous event caused more Bots to be centrally exposed in a short period, so the data for that day may be closer to the lower limit of the true infection scale.

- Infected devices are distributed across multiple global time zones. Affected by time zone differences and usage habits (e.g., turning off devices at night, not using TV boxes during holidays, etc.), these devices are not online simultaneously, further increasing the difficulty of comprehensive observation through a single time window.

- Kimwolf exists in multiple different versions, and the C2s used by different versions are not completely identical, which is also one of the important reasons why we cannot obtain a complete perspective.

Combining the above factors, we conservatively estimate that the actual number of devices infected by Kimwolf has exceeded 1.8 million. A botnet of such scale possesses the capability to launch massive cyberattacks, and its potential destructive power cannot be ignored.

While working hard to track new versions, we were also full of curiosity about the old versions. Through source tracing analysis, although we failed to capture old versions like v1 or v2, we surprisingly found that Kimwolf is actually associated with the Aisuru botnet. Kimwolf relies on an APK file to load and start it during runtime. A DEX file uploaded to VT from India on October 7 showed obvious homologous characteristics with Kimwolf's APK. Subsequently, on October 18, the parent APK of that DEX was uploaded to VT from Algeria; the resource files of this APK contained Aisuru samples for 3 CPU architectures: x86, x64, and arm. We speculate that in the early stages of this campaign, the attackers directly reused Aisuru's code; subsequently, likely because Aisuru samples had high detection rates in security products—Android platforms have more mature security protection systems compared to IoT ecosystems—the group decided to redesign and develop the Kimwolf botnet to enhance stealth and evade detection.

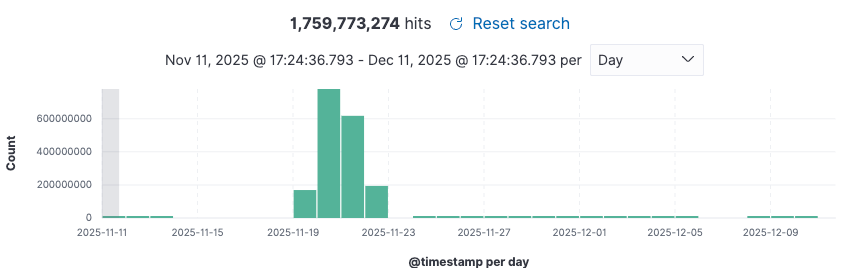

From the monitoring data of the XLab command tracking system, statistics show that the main functions of the Kimwolf botnet are usually concentrated on traffic proxying, with a small amount of DDoS attacks. However, between November 19 and 22, it suddenly went "crazy": in just 3 days, it issued 1.7 billion DDoS attack commands, with the attack range covering massive amounts of IP addresses globally. This high-profile spree follows on the heels of the C2 domain's unprecedented rise to #1 in global popularity. Theoretically, such a large number of attack commands and targets may not be able to produce substantial attack effects on the targets; this behavior may have been purely to demonstrate its own presence.

Currently, the security community's understanding of Kimwolf presents a polarized situation. Information in the public intelligence field is scarce, its propagation path is not yet clear, and the detection rate of related samples and their C2 domains on VirusTotal is extremely low. At the same time, due to the adoption of covert technologies like (DoT), the association between its C2 and samples has not been effectively discovered. However, at the non-public threat confrontation level, the situation is entirely different. We observed that Kimwolf's C2 domains have been successfully taken down by unknown parties at least three times, forcing it to upgrade its tactics and turn to using ENS (Ethereum Name Service) to harden its infrastructure, demonstrating its powerful evolutionary capability. Given that Kimwolf has formed a massive attack scale, and its recent activity frequency and attack behaviors show a significant upward trend, we believe it is necessary to break the intelligence silence. We hereby release this technical analysis report to make relevant research results public, aiming to promote threat intelligence sharing, gather community strength to jointly respond to such threats, and effectively maintain cyberspace security.

Timeline

- October 24: A trusted community partner provided us with the first Kimwolf sample, version v4.

- November 1 to 28: The Xlab Large-scale Network Threat Perception System independently captured 8 new samples, covering v4 and v5 versions.

- December 1: Xlab successfully took over a C2 domain in version v5, observing a peak daily active bot IP count of approximately 1.83 million.

- December 4: A Kimwolf C2 domain was taken down by an unknown party; the C2 domain could not resolve to a valid IP address.

- December 6: Xlab captured a new v5 sample again, which enabled 6 new C2 domains.

- December 8: An active downloader server was discovered in the wild, and scripts related to Kimwolf activities were successfully captured.

- December 10: Kimwolf's new C2 domain was taken down again.

- December 11: Xlab captured a new v5 sample again; this sample enabled a brand new C2 domain, but the C2 port was not open; the parent APK certificate was updated.

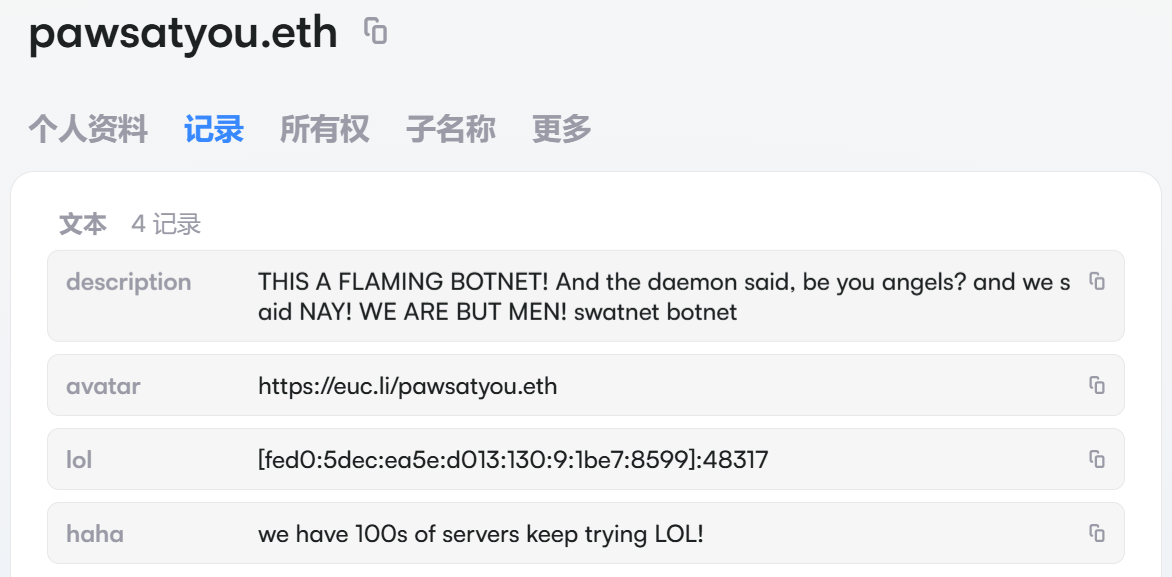

- December 12: Kimwolf upgraded its infrastructure again, enhancing C2 resilience by introducing ENS domains in response to the multiple previous takedowns, even arrogantly declaring "we have 100s of servers keep trying LOL!"

Scale & Capability

On December 1, we successfully took over a Kimwolf C2 domain, allowing us to directly assess the true infection scale of this botnet for the first time. Statistically, the cumulative infected IPs exceeded 3.66 million, reaching an activity peak on December 4 with single-day node IPs as high as 1,829,977. Our takeover action seemed to trigger a chain reaction, followed by unknown third parties implementing takedowns (such as stopping DNS resolution) on Kimwolf's other C2 infrastructures. This forced Kimwolf's operators to perform emergency upgrades, completely replacing the sample's C2 configurations, which caused the numbers we observed to drop sharply. currently, the daily active scale is around 200,000.

Kimwolf mainly targets the Android platform, involving TVs, set-top boxes, tablets, and other devices. Some device models are shown below:

| Device Model | Device Model | Device Model | Device Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| TV BOX | SuperBOX | HiDPTAndroid | P200 |

| X96Q | XBOX | SmartTV | MX10 |

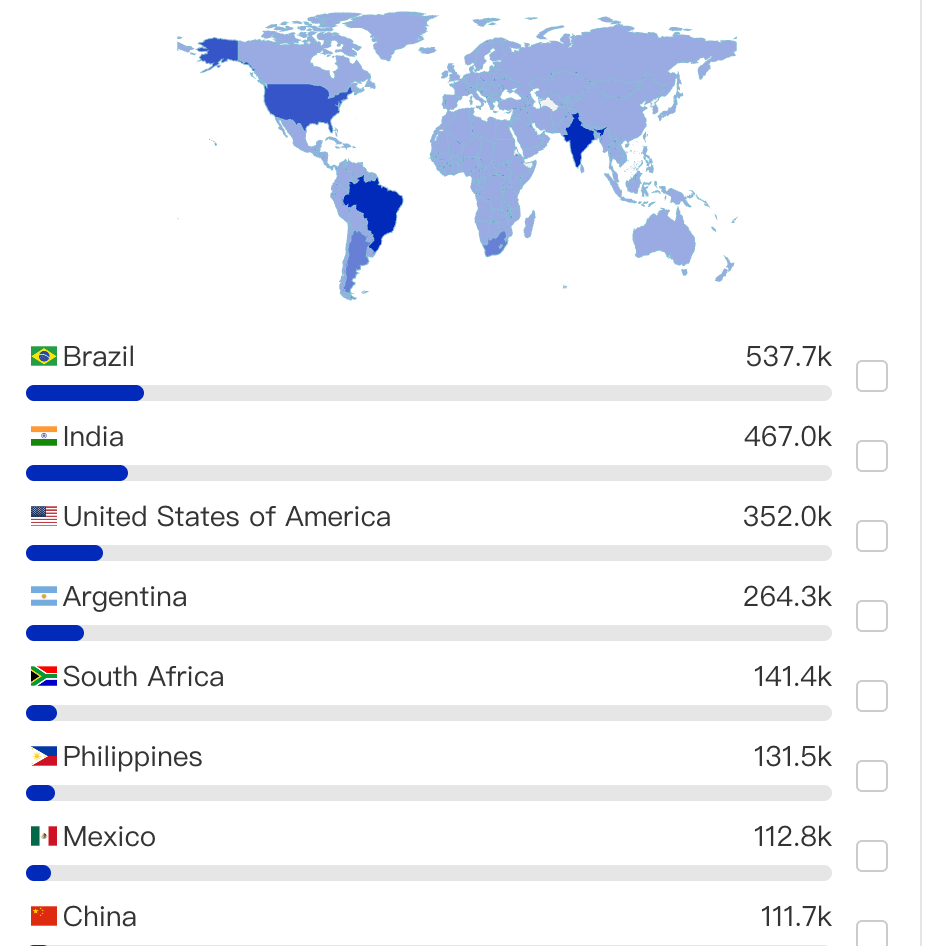

Infected devices are distributed in 222 countries and regions globally. The top 15 countries are analyzed as: Brazil 14.63%, India 12.71%, USA 9.58%, Argentina 7.19%, South Africa 3.85%, Philippines 3.58%, Mexico 3.07%, China 3.04%, Thailand 2.46%, Saudi Arabia 2.37%, Indonesia 1.87%, Morocco 1.85%, Turkey 1.60%, Iraq 1.53%, Pakistan 1.39%.

Readers familiar with DDoS might be curious: "For such a huge botnet, what level has its attack capability actually reached?" Although we cannot directly measure it, through observations of two large-scale DDoS events and a horizontal comparison with Aisuru, we believe Kimwolf's attack capability is close to 30Tbps.

- A well-known cloud service provider observed a 2.3Bpps attack at 22:09Z on November 23, with 450,000 participating IPs. We confirmed Kimwolf's participation.

- A well-known cloud service provider observed an attack nearing 30Tbps and 2.9Gpps at 09:35Z on December 9. After data comparison, both parties confirmed Kimwolf's participation.

- Cloudflare pointed out in its Q3 2025 DDoS threat report that Aisuru is one of the strongest known botnets currently, with a control scale of millions of IoT/network devices, capable of sustaining Tbps-level attacks and even peak attacks approaching 30 Tbps and 10+ Bpps.

In fact, we believe that behind many attacks observed by Cloudflare attributed to Aisuru, it may not just be the Aisuru botnet acting alone; Kimwolf may also be participating, or even led by Kimwolf. These two major botnets propagated through the same infection scripts between September and November, coexisting in the same batch of devices. They actually belong to the same hacker group.

Kimwolf & Aisuru

How did we uncover the connection between Kimwolf and Aisuru? It all started with the APK sample (MD5: b688c22aabcd83138bba4afb9b3ef4fc) captured on October 25. The file and package names were aisuru.apk and com.n2.systemservice0644, respectively. This sample implemented a malicious Android boot receiver, enabling automatic execution upon device startup.

Its main malicious behavior is: extracting a preset binary file (referenced via resource ID R.raw.libniggakernel) from the application's own res/raw/ resource directory, writing it to the application data directory named niggakernel, and then setting the file permission to executable. Subsequently, the sample attempts to obtain root privileges via the su command to execute this malicious program, achieving persistence and system control.

Upon analysis, this preset binary file ji.so is essentially the "kimwolf" malware. The sample previously provided to us by the security community was exactly the unpacked version of this file.

Using various features of the aforementioned APK as clues, we found that the APK (MD5: 887747dc1687953902488489b805d965) has obvious homologous characteristics, such as using the same resource ID name libniggakernel, the same package name systemservice0644, Log identifier "LOL", preset filename ji.so, etc.

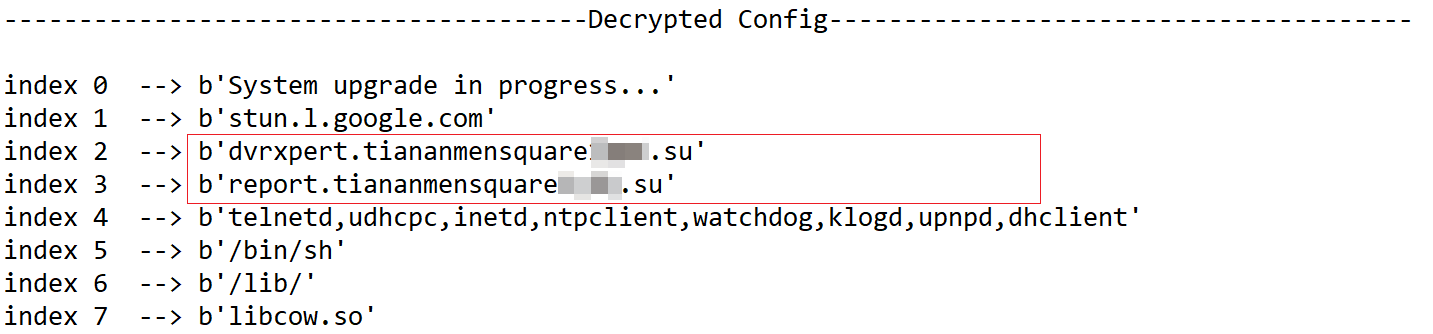

What surprised us is that the 3 binary files c0.so, ji.so, and q8.so preset in this APK do not belong to the kimwolf family, but to the AISURU botnet. They use the same C2 and Reporter as the sample 053a0abe0600d16a91b822eb538987bca3f3ab55 mentioned in our September 15 analysis report.

On November 29, more evidence surfaced. Two APK samples uploaded to VirusTotal successively from the United States were highly similar to the two APKs above. Upon analysis, the libdevice.so in their lib directories corresponded to new variants of "kimwolf" and "aisuru" respectively.

- 902cf9a76ade062a6888851b9d1ed30d

Family: kimwolf

Package Name: com.n2.systemservice063

lib file directory: /lib/armeabi-v7a/libdevice.so - 8011ed1d1851c6ae31274c2ac8edfc06

Family: aisuru

Package Name: com.n2.systemservice062

lib file directory: /lib/armeabi-v7a/libdevice.so

More crucially, these two APKs used the same signing certificate. The certificate SHA1 fingerprint is 182256bca46a5c02def26550a154561ec5b2b983. The content features of this certificate, such as Common Name: John Dinglebert Dinglenut VIII VanSack Smith, are highly unique and have no public record on the internet. From this, it can be judged that they come from the hands of the same development organization.

On December 8, we finally had definitive evidence. The script captured on the Downloader server 93.95.112.59 directly associated kimwolf (mreo31.apk) and aisuru (meow217) together.

Cautious readers might ask: "Is there a possibility that the Aisuru group's code was leaked or sold to a third party?" Frankly speaking, this possibility does exist. Fortunately, although the C2 addresses of the Aisuru samples captured on November 29 mentioned above were updated, they still reused the previously named tiananmeng Reporter. The reuse of infrastructure strongly eliminates the possibility of third-party code reuse. In summary, we have high confidence in attributing Kimwolf to the Aisuru group.

Technical Details

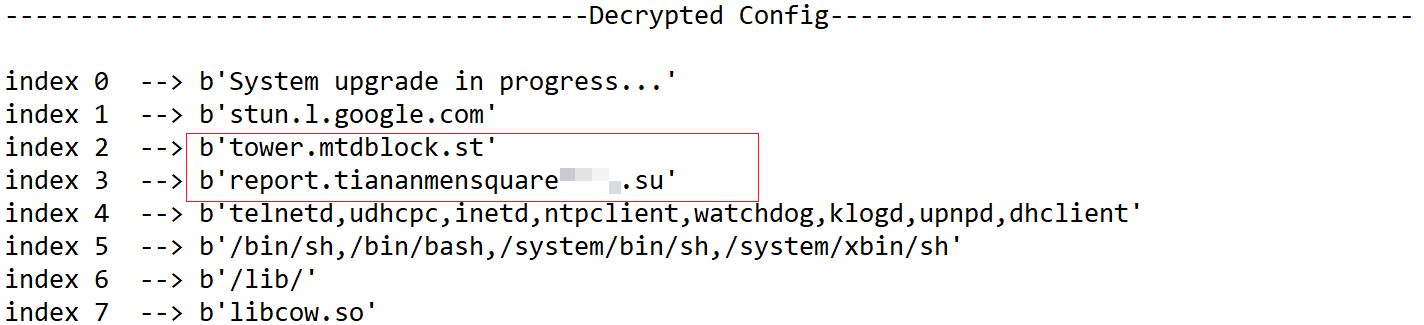

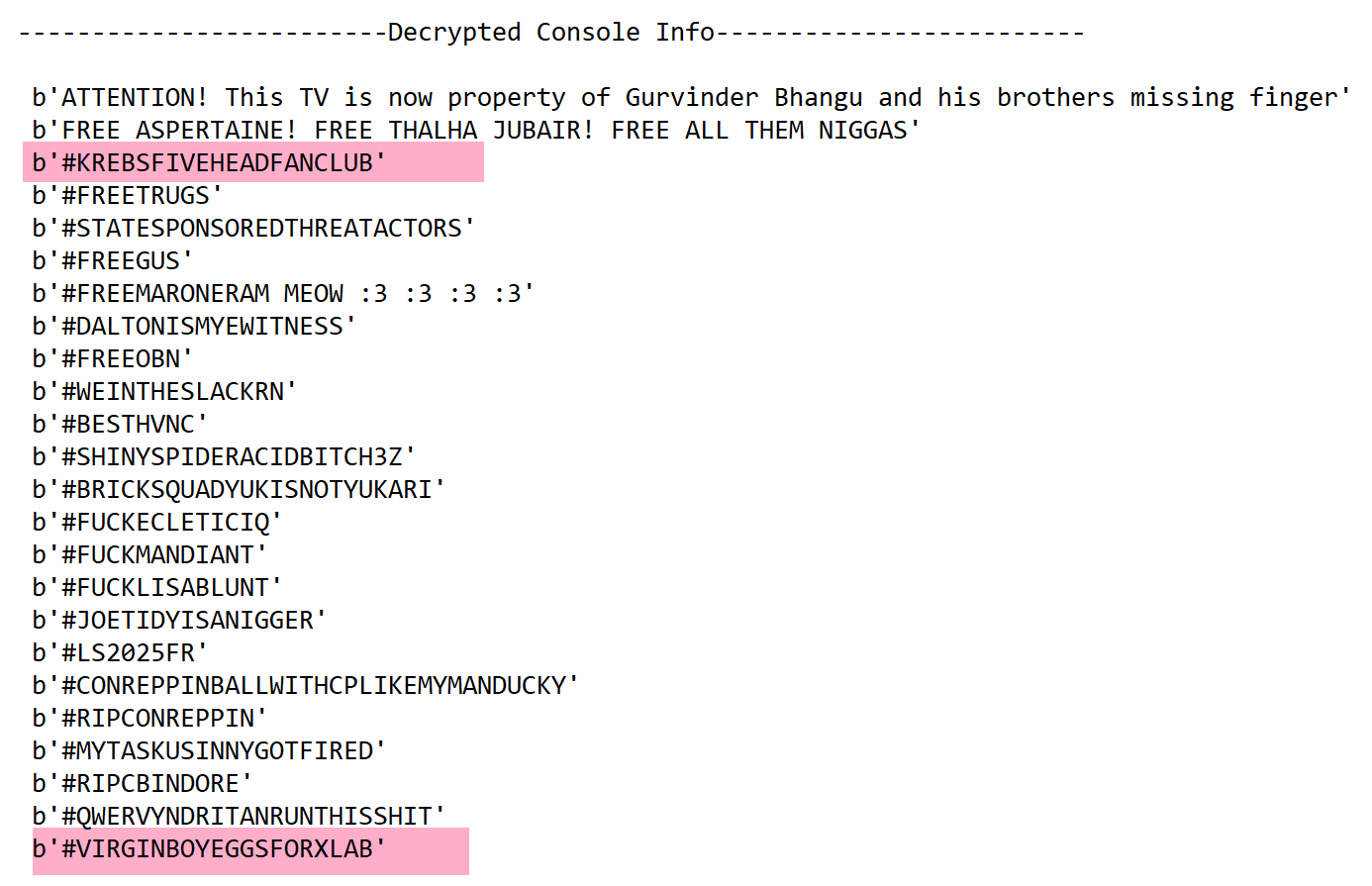

The Kimwolf samples we captured can be divided into two major versions: v4 and v5. In v4, Kimwolf's author, either out of bad taste or to express political attitudes, liked to output various information in the console.

- sample 18dcf61dad028b9e6f9e4aa664e7ff92 outputs

$$ ForeheadSDK v2.0 Premium Edition $$; - sample 2078af54891b32ea0b1d1bf08b552fe8 outputs

Kim Jong-un Leads Our Nation to Strength. Long live our Supreme Leader!.

The most exaggerated one is sample 1c03d82026b6bcf5acd8fc4bcf48ed00, which, besides outputting a series of political views, specifically mocked the well-known cybersecurity investigative journalist Krebs, calling him "Big Forehead" (KREBSFIVEHEADFANCLUB), and even jokingly asked the Xlab team to "taste virgin boy eggs" (VIRGINBOYEGGSFORXLAB).

Kimwolf's author is quite vengeful. After we preemptively registered their C2, they immediately counterattacked, leaving an "easter egg" in the DDoS attack method of ssl_socket to stigmatize Chinese people. regarding this, we just want to say: "Sooner or later, you'll taste our iron fist."

idontlikemchineseniggas

becausetheylikeitrealyoung

myniggatheylikeit131415.com

The core malicious functions of v4 and v5 versions are highly consistent. The execution flow of these samples can be summarized as follows: after the sample starts on the infected device, it first achieves single instance by creating a file socket to ensure only one process runs continuously on the same device; subsequently, it decrypts the embedded C2 domain, and to evade conventional detection, uses the DNS-over-TLS protocol to initiate queries to the port 853 of public DNS services (8.8.8.8 or 1.1.1.1) to obtain the real C2 IP; finally, it establishes a communication connection with that IP, entering a waiting state, ready to receive and execute commands from the control end at any time.

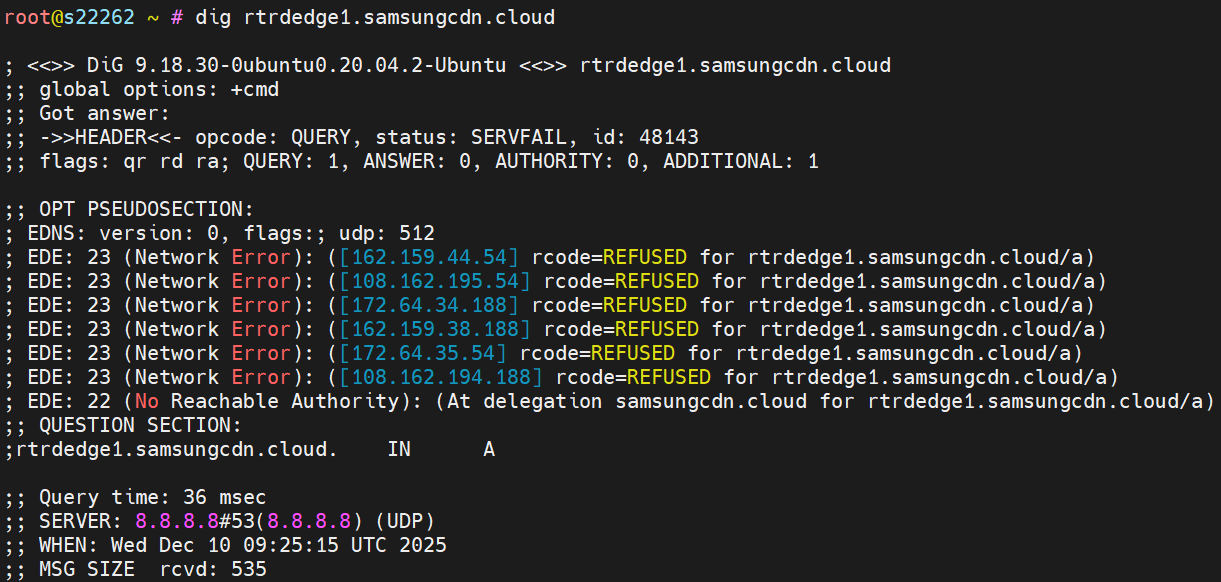

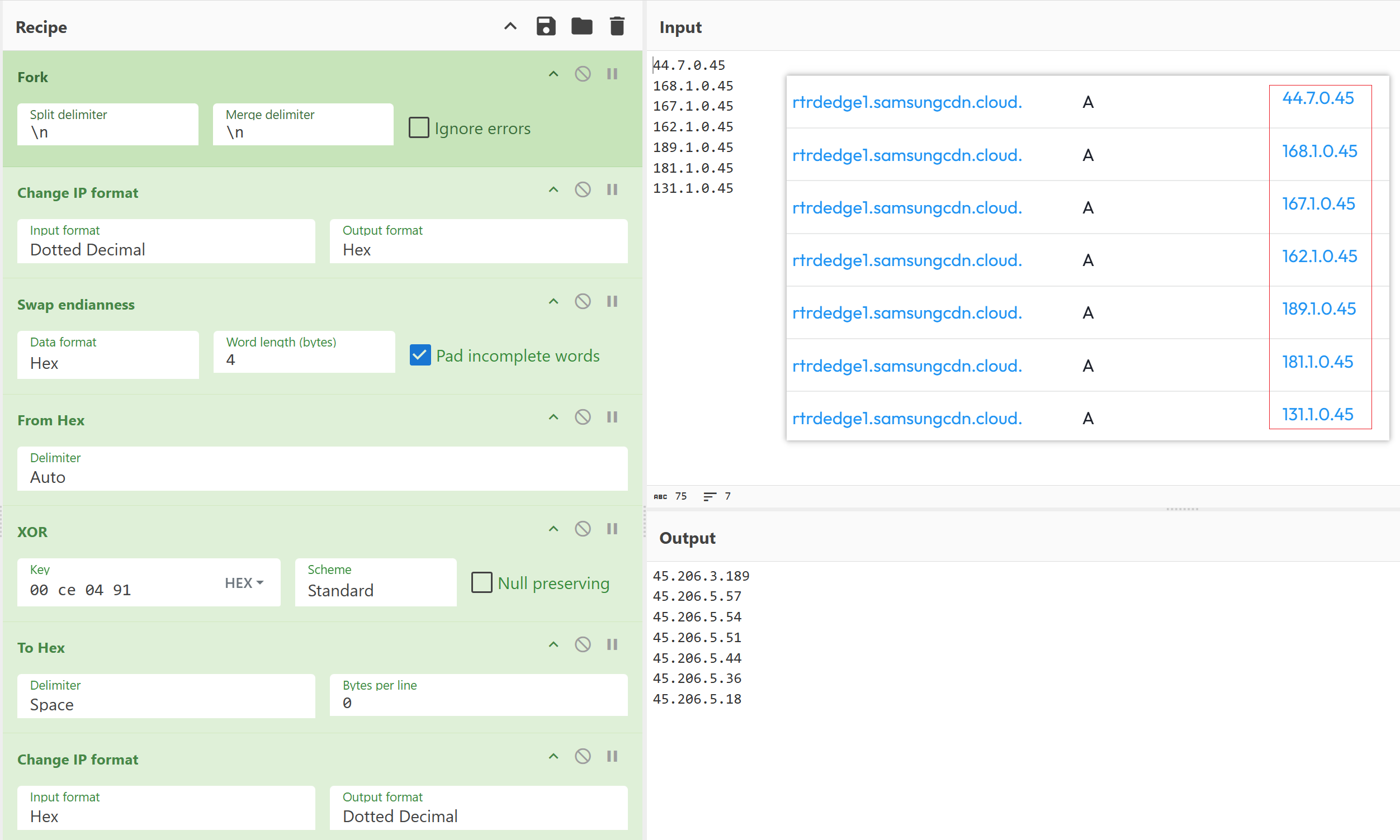

The most significant difference between v4 and v5 versions lies in the method of obtaining the real C2 IP: v4 version directly uses DNS to query the A record of the C2 domain, while v5 version, after querying the IP, requires an XOR operation. Taking C2 domain rtrdedge1.samsungcdn[.]cloud as an example, the IP resolved on December 3 was 44.7.0.45; after XORing with 0xce0491, the real C2 IP 45.206.3.189 is obtained.

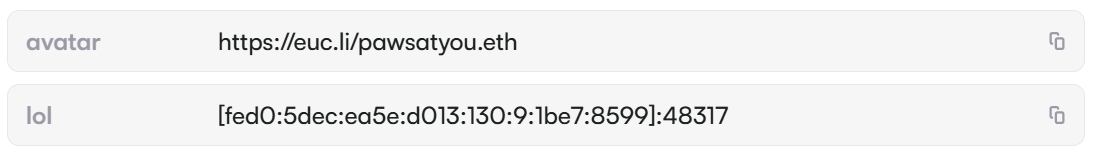

On December 12, Kimwolf began using EtherHiding technology. The sample introduced an ENS domain (Ethereum Name Service), pawsatyou.eth, with the C2 hidden in the "lol" text record.

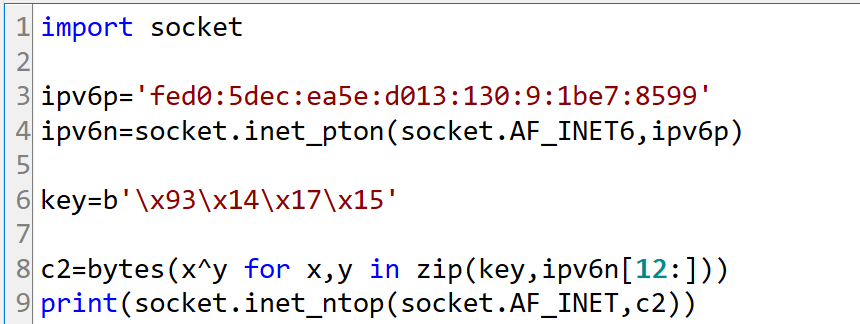

But the real C2 is not the IPv6 in "lol", but rather obtained by taking the last 4 bytes of the address and performing an XOR operation to get the real IP. Taking fed0:5dec:ea5e:d013:130:9:1be7:8599 as an example, taking the last 4 bytes 1b e7 85 99 and XORing with 0x93141715 yields the real C2 IP 136.243.146.140.

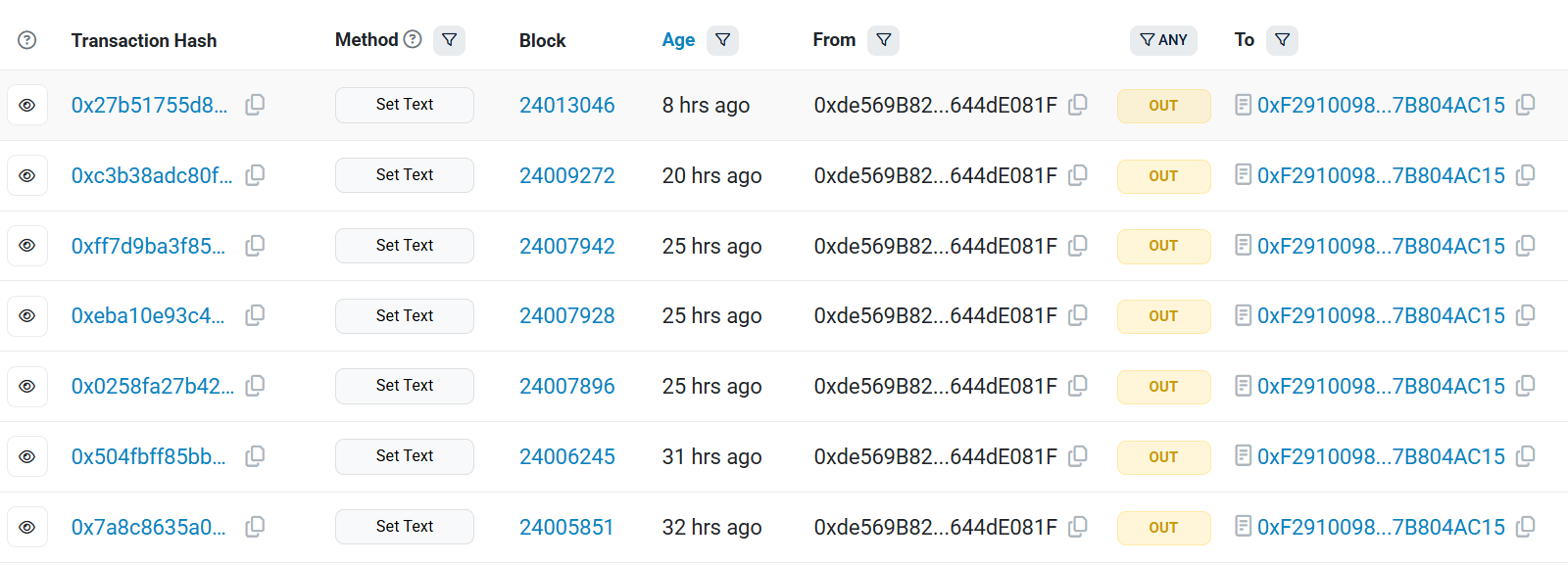

The technical essence of ENS is a system of smart contracts deployed on Ethereum. The contract address for pawsatyou.eth is 0xde569B825877c47fE637913eCE5216C644dE081F. Readers familiar with smart contracts will not find it difficult to understand the advantage behind this design: Kimwolf implements a channel similar to cloud configuration for C2 via the contract. Even if the C2 IP is taken down, the attacker only needs to update the lol record to quickly issue a new C2. And this channel itself relies on the decentralized nature of blockchain, unregulated by Ethereum or other blockchain operators, and cannot be blocked.

Overall, Kimwolf's functions are not complex. The following text will take the sample captured on December 9 as the main analysis object to dissect Kimwolf's technical details from aspects of string decryption, single instance, and network protocols.

MD5: 3e1377869bd6e80e005b71b9e991c060

MAGIC: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, ARM, EABI5 version 1 (GNU/Linux), statically linked, no section header

PACKER: UPX

String Decryption

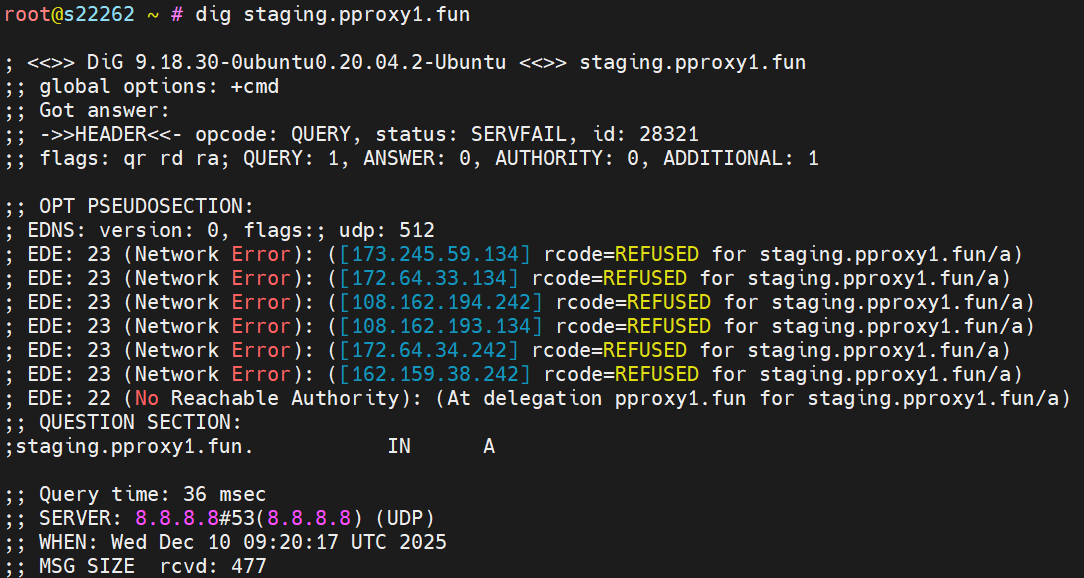

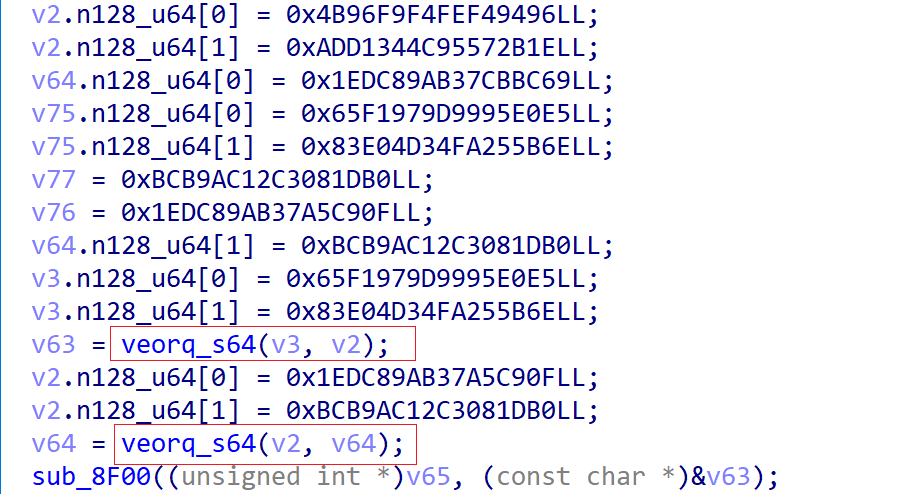

Kimwolf uses simple Stack XOR operations to encrypt sensitive data like C2, DNS Resolver, etc. A large number of similar code snippets can be seen in the pseudo-code decompiled by IDA. veorq_s64 is an 8-byte XOR instruction, so decryption is simple: one can use regex to extract the operands and then perform the XOR. In the figure below, the content decrypted by v63 is exactly the C2 staging.pproxy1[.]fun.

I believe readers who have tried manual decryption will find this very inconvenient and ask if there is a more efficient method. The answer is yes. With a little observation of the code snippet above, we know that the decrypted C2 string is the 2nd parameter of function sub_8F00. Based on this characteristic, we can use an emulator to achieve batch automatic decryption of C2s.

import flare_emu

eh=flare_emu.EmuHelper()

def iterateHook(eh, address, argv, userData):

if eh.isValidEmuPtr(argv[1]):

buf=eh.getEmuString(eh.getRegVal('R1'))

print(f"0x{address:x} ---> {buf}")

eh.iterate(0x00008F00,iterateHook)

The final effect is as follows, successfully decrypting 6 C2s:

The instruction code for veorq_s64 is VEOR Q8, Q8, Q9. Through it, we can locate all functions where encrypted strings are located. Then, based on the patterns presented in different functions, using flare_emu's iterate or emulateRange can conveniently achieve decryption of all sensitive strings.

Single Instance

Kimwolf disguises its own process name as netd_services or tv_helper, and uses a Unix domain socket named @niggaboxv[number] to implement single instance control. This combination of features can be used as a high-confidence Indicator of Compromise (IOC) for device troubleshooting.

Network Protocol

Kimwolf's network communication always uses TLS encryption. In early versions, the application layer protocol was directly carried over the TLS tunnel; in the current version, a websocket handshake is performed before sending the register message, but the protocol is not used subsequently. Its network communication packets follow a fixed "Header + Body" format. In the Header, the Reserved field is a fixed value 1, while the Magic has iterated three times, currently being "AD216CD4"; the structure of the message body varies depending on the message type.

type Header struct {

Magic [4]byte // "DPRK" -> "FD9177FF" -> "AD216CD4"

Reserved uint8 // 1

MsgType uint8

MsgID uint32

BodyLen uint32

CRC32 uint32

}

The MsgType field is used to explain the message type. Its values and corresponding functions are shown in the table below:

| MsgType | desc |

|---|---|

| 0 | register |

| 1 | verify |

| 2 | confirm |

| 3 | heartbeat |

| 4 | reconnect |

| 5 | tcp proxy |

| 6 | udp proxy |

| 7 | reverse shell |

| 8 | cmd execute |

| 9 | write file |

| 10 | read file |

| 12 | ddos attack |

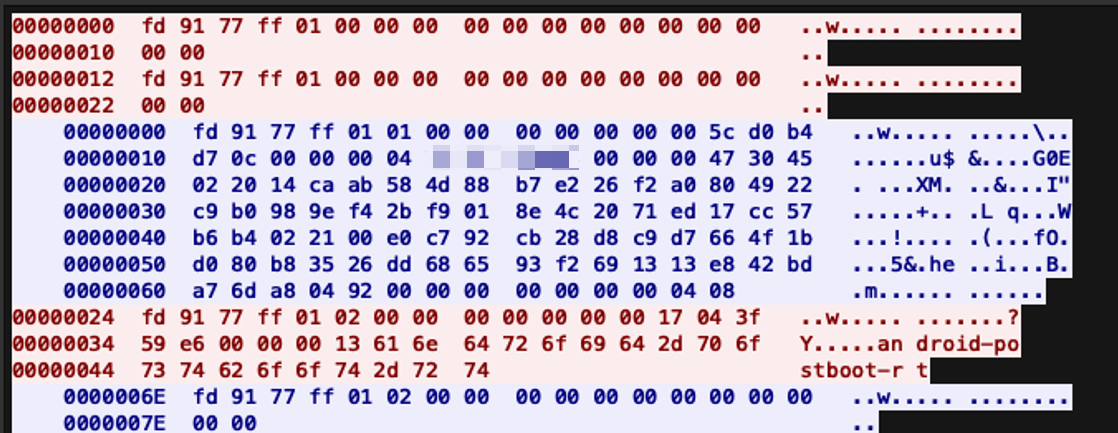

Communication initialization between the Bot and C2 server adopts a three-stage handshake mechanism. Both parties must sequentially complete the three interactions of register, verify, and confirm to achieve two-way identity authentication before it is considered a trusted session established.

Next, let's explain the interaction process between Bot and C2 using actually generated network traffic.

Step 1: Register, Bot ---> C2

The Bot sends two 18-byte Headers to the C2, where MsgType is 0, MsgID, BodyLen, CRC32 fields are all 0, and Magic is FD9177FF.

Step 2: Verify, C2 ---> Bot

The C2 generates an Elliptic Curve Digital Signature for a random message using a private key and constructs the packet Body part in the following format.

type VerifyBody struct {

MsgLen uint32

Msg []byte

SigLen uint32

Sig []byte

}

Parsing the Body in the example according to the above structure reveals:

- MsgLen is 4 bytes

- Msg is

xx xx xx xx - SigLen is 0x47 bytes

- Signature

#Signature

00000000 30 45 02 20 14 ca ab 58 4d 88 b7 e2 26 f2 a0 80 |0E. .Ê«XM.·â&ò .|

00000010 49 22 c9 b0 98 9e f4 2b f9 01 8e 4c 20 71 ed 17 |I"É°..ô+ù..L qí.|

00000020 cc 57 b6 b4 02 21 00 e0 c7 92 cb 28 d8 c9 d7 66 |ÌW¶´.!.àÇ.Ë(ØÉ×f|

00000030 4f 1b d0 80 b8 35 26 dd 68 65 93 f2 69 13 13 e8 |O.Ð.¸5&Ýhe.òi..è|

00000040 42 bd a7 6d a8 04 92 |B½§m¨..|

When the Bot receives the Verify packet, it uses the hardcoded public key to verify the signature. Once verified, it enters the final Confirm stage. The author of Kimwolf designed this mechanism with the intention of protecting their C2 network from being taken over by others.

# Publickey

00000000 30 59 30 13 06 07 2a 86 48 ce 3d 02 01 06 08 2a |0Y0...*.HÎ=....*|

00000010 86 48 ce 3d 03 01 07 03 42 00 04 ed 6a a0 57 2d |.HÎ=....B..íj W-|

00000020 53 02 ce 35 cc 0a 04 93 2d b4 86 c9 a8 e2 93 f5 |S.Î5Ì...-´.ɨâ.õ|

00000030 69 07 86 0f 99 42 4b a6 5c 12 7a e7 12 48 56 ad |i....BK¦\.zç.HV.|

00000040 34 b5 ae 92 ec 98 c9 bc e1 d8 15 dc 6e 1c 59 1b |4µ®.ì.ɼáØ.Ün.Y.|

00000050 be 96 b8 a9 5b 95 46 34 19 5a d2 |¾.¸©[.F4.ZÒ|

Step 3: Confirm, Bot -> C2

The Bot uses the first parameter passed at runtime as the group identifier, constructs it according to the GroupBody structure, and reports it to the C2. The group string used in the example is "android-postboot-rt".

type GroupBody struct {

MsgLen uint32

Group []byte

}

Step 3: Confirm, C2 -> BOT

After receiving the Bot's Confirm packet, the C2 server checks whether its belonging group has been pre-enabled in the campaign. If the match is successful, the Bot's identity is confirmed as legal, and a Confirm response packet is sent back to it. The MsgType field value of this response packet is 2, and MsgID, BodyLen, CRC32 fields are all set to 0.

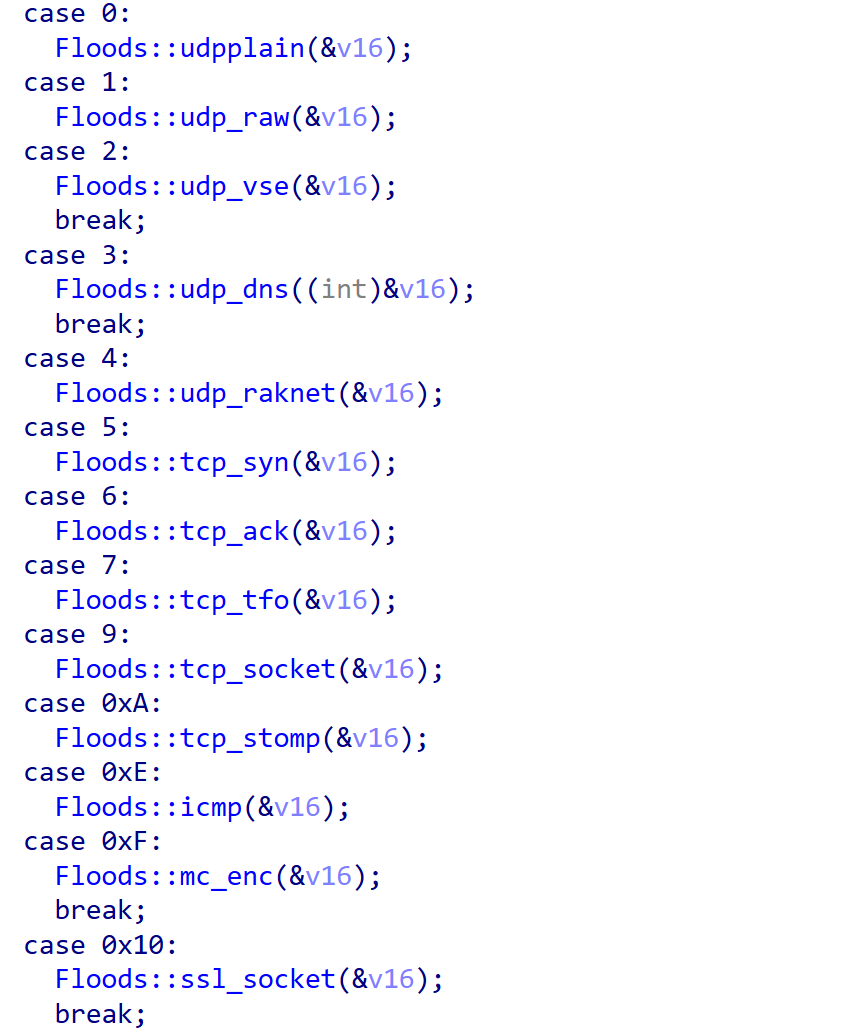

After the above process, the Bot and C2 complete the two-way identity authentication, and the Bot begins waiting to execute commands sent by the C2. When the command number is 12, Kimwolf executes DDoS-related functions. I believe readers familiar with Mirai will smile knowingly when seeing the DDoSBody, as this structure originates exactly from Mirai.

Type DDoSBody struct {

AtkID uint32

AtkType uint8

Duration uint32

TargetCnt uint32

Targets []Target

FlagCnt uint32

Flags []Flag

}

Below are the 13 DDoS attack methods supported by Kimwolf.

Command Tracking

Data from Xlab shows that the main command of the Kimwolf botnet is to use Bot nodes to provide proxy services, accounting for 96.5% of all commands. The rest are DDoS attack commands. DDoS attack targets are spread across various industries globally. Attack targets are mainly concentrated in regions like the USA, China, France, Germany, and Canada.

1.7 Billion in 3 Days

From November 19 to 22, in just 3 short days, Kimwolf issued a staggering 1.7 billion commands, randomly attacking massive amounts of IP addresses globally. We don't know why it had such confusing attack behavior, as these attacks might not even cause substantial damage to the target addresses. We even once suspected whether a BUG produced by ourselves caused these anomalies. It wasn't until we verified data with multiple top cloud service providers that we finally confirmed—Kimwolf is just that crazy; it indeed sprayed the entire internet.

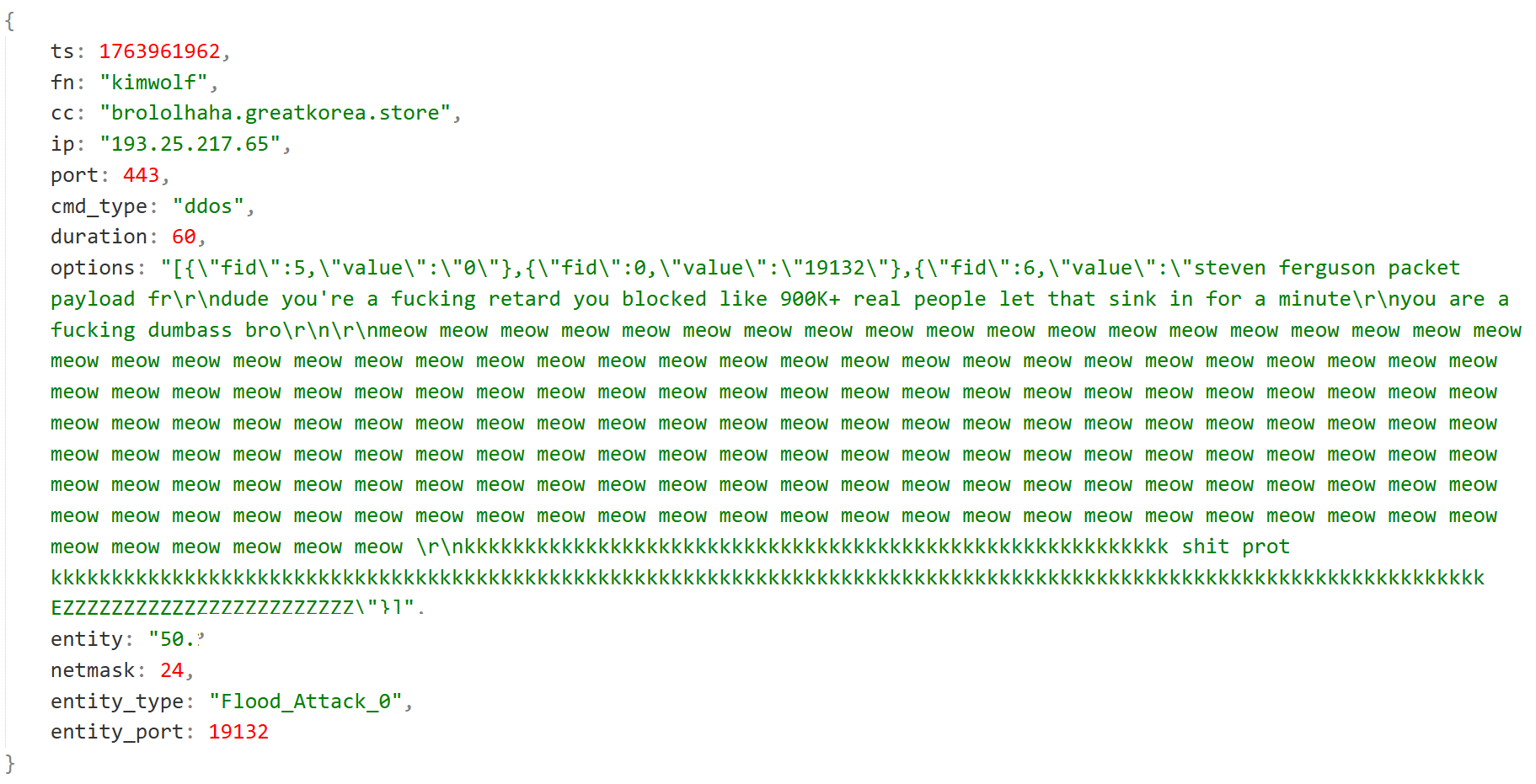

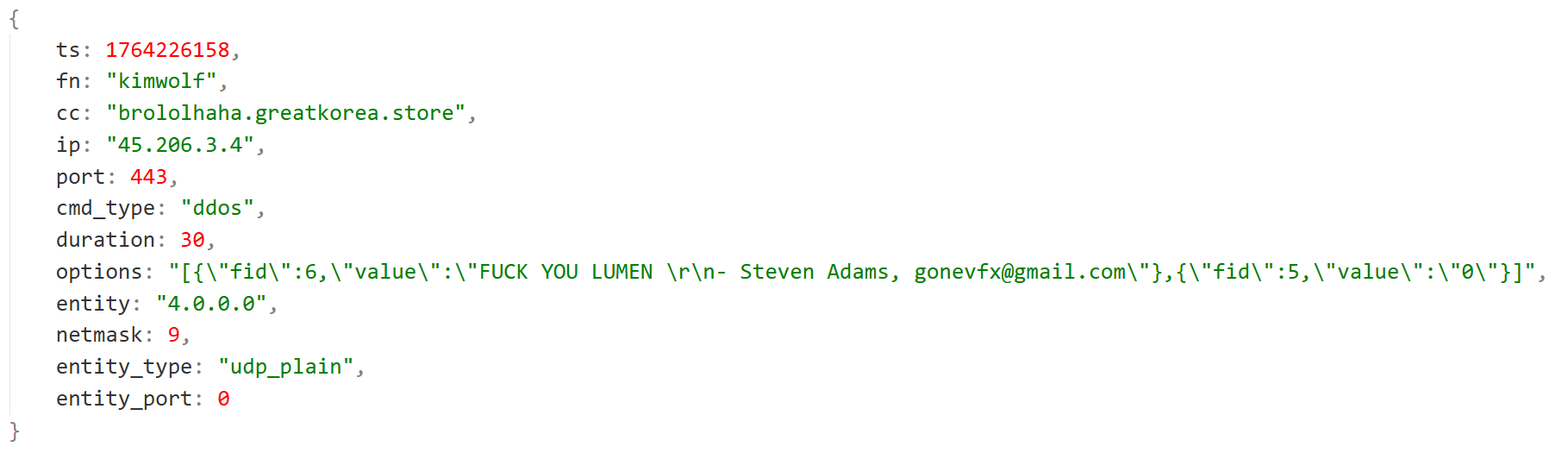

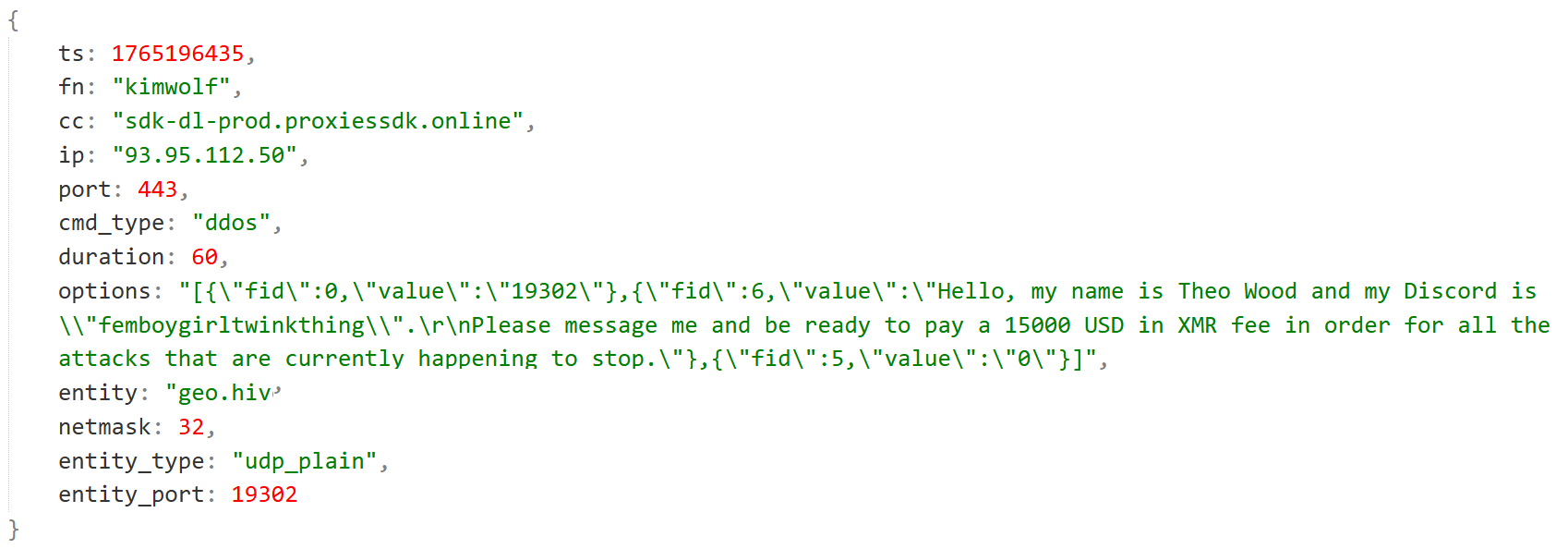

Arrogant Attack Payloads

Kimwolf often includes various ridicule, provocation, and even extortion information in DDoS Payloads.

- Ridicule

- Provocation

- Extortion

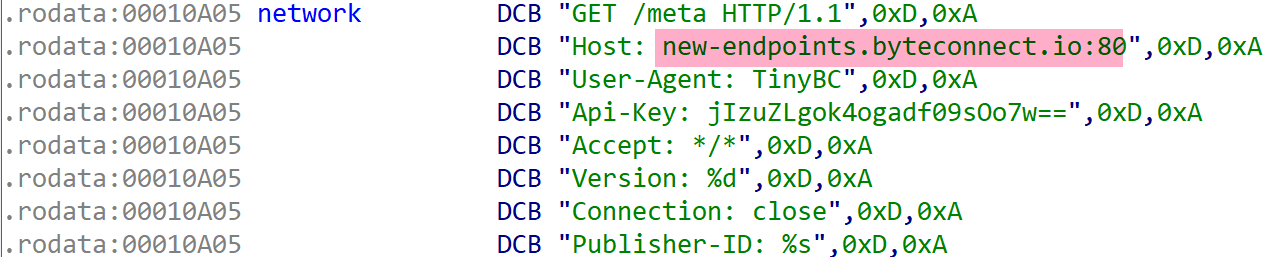

Additional Components

In this campaign, to maximize the bandwidth extraction from compromised devices and maximize profit, the attackers deployed a Rust-based Command Client and ByteConnect SDK in addition to Kimwolf and Aisuru.

1: Command Client

The purpose of the Command Client is to form a proxy network. It targets proxying socks, receives proxy requests from C2, and returns proxy results to C2.

The sample saves the CC address in ciphertext in the rodata section. The decryption algorithm is not complex, being a byte-wise XOR with a password table of the same length.

def dec(encbts):

tb1_off = 0

tb2_off = 0x058BCD2 - 0x058BCA0

bts = []

for i in range(0, 0x30*4):

bts.append(chr(encbts[tb1_off+i] ^ encbts[tb2_off+i]))

return("".join(bts[:0x32]))

Based on the samples we have, two CC addresses can be restored, as follows:

proxy-sdk.14emeliaterracewestroxburyma02132.su:443

sdk-bright.14emeliaterracewestroxburyma02132.su:443

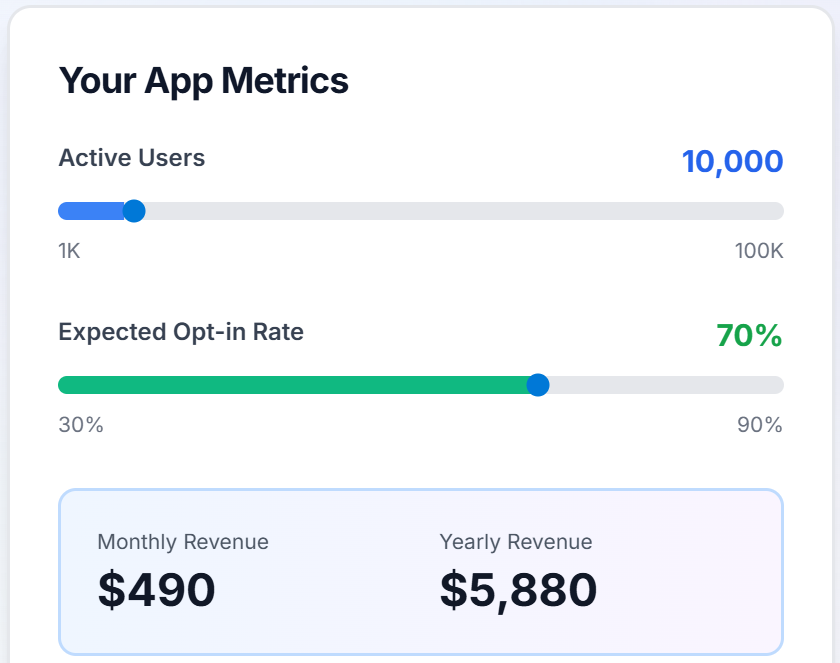

2: ByteConnect SDK

The so-called ByteConnect SDK is a monetization solution that helps developers generate revenue through applications on various platforms. They claim their SDK is designed to be lightweight, secure, and easy to integrate; it is ad-free, has no cryptocurrency mining, does not affect performance, has minimal impact on user experience, and users won't even notice its existence.

mreo12 downloaded by the Downloader script is exactly the ByteConnect SDK.

ByteConnect's homepage has a revenue calculation formula: 10,000 access point users, 70% Opt-in Rate, will yield $490 monthly revenue. With Kimwolf's scale of 1.8 million, the organization behind it earns an astonishing $88,200 monthly through ByteConnect.

Little Gossip

Investigations found that the author of Kimwolf shows an almost "obsessive" fixation on the well-known cybersecurity investigative journalist Brian Krebs, leaving easter eggs related to him in multiple samples.

For example, in sample 2078af54891b32ea0b1d1bf08b552fe8, the domain fuckbriankrebs[.]com is embedded in both its udp_dns and mc_enc attack methods, used to generate DNS request payloads.

And in the console output of sample 1c03d82026b6bcf5acd8fc4bcf48ed00, the text KREBSFIVEHEADFANCLUB appears directly, literally "Krebs Big Forehead Fan Club,". Talk about a dedicated 'hater'.

Besides this direct "tribute," there is "love" hidden deeper. The C2 domain we took over fuckyoukrebs1.briankrabs.seanobrien[redacted]ssn[redacted].su, aside from the string 'krebs' appearing twice in the domain itself, hides a mystery: seanobrien[redacted] likely corresponds to Krebs' actual address, and ssn[redacted] is likely his Social Security Number. Such behavior can be called a "sasaeng fan" in the cyber security world, truly chilling.

Summary

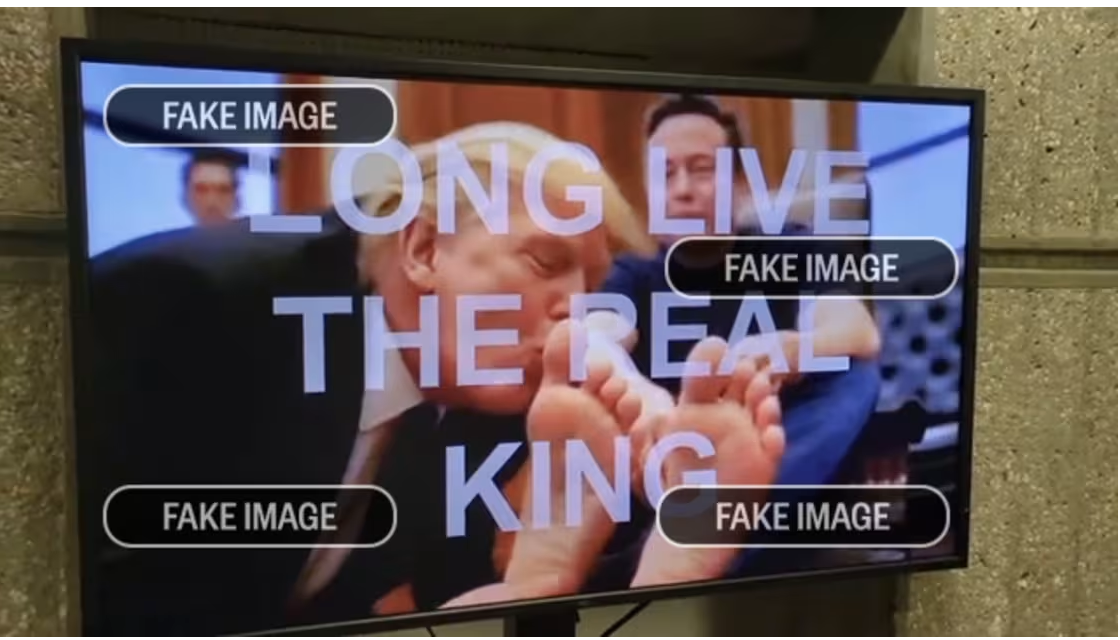

This is the majority of the intelligence we currently possess on the Kimwolf botnet. Giant botnets originated with Mirai in 2016, with infection targets mainly concentrated on IoT devices like home broadband routers and cameras. However, in recent years, information on multiple million-level giant botnets like Badbox, Bigpanzi, Vo1d, and Kimwolf has been disclosed, indicating that some attackers have started to turn their attention to various smart TVs and TV boxes. These devices generally suffer from problems like firmware vulnerabilities, pre-installed malicious components, weak passwords, and lack of security update mechanisms, making them extremely easy for attackers to control long-term and use for large-scale cyberattacks. One of our motives for disclosing the Kimwolf botnet this time is to call on the security community to give due attention to smart TV-related devices.

After attackers gain root privileges on smart TVs, the resulting attacks are not limited to traditional cyberspace. Attackers can use controlled terminals to insert tampered, biased, or extreme videos. In the legal systems of many countries, inserting content without written permission violates the contract between the viewer and the TV program provider and is illegal. For example, TV equipment at the HUD headquarters in Washington, D.C., USA, was tampered with by hackers to play an unauthorized AI-forged video (showing Trump kissing Musk's toes, with the caption LONG LIVE THE REAL KING), triggering significant public safety and public opinion risks, etc. This is our second motive for disclosing the Kimwolf botnet this time, calling on law enforcement agencies to consider scrutinizing such suspected illegal activities related to smart TVs.

Against the backdrop of overlapping threats, whether ordinary TV box users, sales channels, operators, or regulatory departments and manufacturers, all must attach great importance to the security of TV boxes. Among them, TV box users should especially: ensure devices come from reliable sources, use firmware that can be updated in time, avoid setting weak passwords, and refuse to install APKs of unknown origin to reduce the risk of being infected and controlled by botnets.

We sincerely welcome CERTs from all countries to contact us, share intelligence and vision, join hands to combat cybercrime, and jointly maintain global cybersecurity. If you are interested in our research, or know inside information, feel free to contact us via X platform.

IOC

Sample MD5

# APK

887747dc1687953902488489b805d965

b688c22aabcd83138bba4afb9b3ef4fc

2fd5481e9d20dad6d27e320d5464f71e

5f4ed952e69abb337f9405352cb5cc05

4cd750f32ee5d4f9e335751ae992ce64

8011ed1d1851c6ae31274c2ac8edfc06

95efbc9fdc5c7bcbf469de3a0cc35699

bda398fcd6da2ddd4c756e7e7c47f8d8

ea7e4930b7506c1a5ca7fee10547ef6b

dfe8d1f591d53259e573b98acb178e84

3a172e3a2d330c49d7baa42ead3b6539

# SO ELF

726557aaebee929541f9c60ec86d356e

bf06011784990b3cca02fe997ff9b33d

d086086b35d6c2ecf60b405e79f36d05

2078af54891b32ea0b1d1bf08b552fe8

b89ee1304b94f0951af31433dac9a1bd

34dfa5bc38b8c6108406b1e4da9a21e4

51cfe61eac636aae33a88aa5f95e5185

1c03d82026b6bcf5acd8fc4bcf48ed00

e96073b7ed4a8eb40bed6980a287bc9f

f8a70ca813a6f5123c3869d418f00fe5

33435ec640fbd3451f5316c9e45d46e8

9053cef2ea429339b64f3df88cad8e3f

85ba20e982ed8088bb1ba7ed23b0c497

9b37f3bf3b91aa4f135a6c64aba643bd

# RUST

b1d4739d692d70c3e715f742ac329b05

5490fb81cf24a2defa87ea251f553d11

cf7960034540cd25840d619702c73a26

# Downloader

e4be95de21627b8f988ba9b55c34380c

C2

api.groksearch[.net

nnkjzfaxkjanxzk.14emeliaterracewestroxburyma02132[.su

zachebt.chachasli[.de

zachebt.groksearch[.net

rtrdedge1.samsungcdn[.cloud

fuckzachebt.meowmeowmeowmeowmeow.meow.indiahackgod[.su

staging.pproxy1[.fun

sdk-dl-prod.proxiessdk[.online

sdk-dl-production.proxiessdk[.store

lol.713mtauburnctcolumbusoh43085[.st

pawsatyou[.eth

lolbroweborrowtvbro.713mtauburnctcolumbusoh43085[.st

Downloader

93.95.112.50 AS397923 - Resi Rack L.L.C.

93.95.112.51 AS397923 - Resi Rack L.L.C.

93.95.112.52 AS397923 - Resi Rack L.L.C.

93.95.112.53 AS397923 - Resi Rack L.L.C.

93.95.112.54 AS397923 - Resi Rack L.L.C.

93.95.112.55 AS397923 - Resi Rack L.L.C.

93.95.112.59 AS397923 - Resi Rack L.L.C.

Appendix

cyberchef

https://gchq.github.io/CyberChef/#recipe=Fork('%5C%5Cn','%5C%5Cn',false)Change_IP_format('Dotted%20Decimal','Hex')Swap_endianness('Hex',4,true)From_Hex('Auto')XOR(%7B'option':'Hex','string':'00%20ce%2004%2091'%7D,'Standard',false)To_Hex('Space',0)Change_IP_format('Hex','Dotted%20Decimal')&input=NDQuNy4wLjQ1CjE2OC4xLjAuNDUKMTY3LjEuMC40NQoxNjIuMS4wLjQ1CjE4OS4xLjAuNDUKMTgxLjEuMC40NQoxMzEuMS4wLjQ1